Blinding (masking)

How blinding or masking makes your findings more robust, when to use it and how to create a blinding plan.

- Why is blinding important?

- Allocation concealment and blinding during and after intervention

- Blinding during conduct of the experiment

- Blinding during result assessment

- Blinding during analysis of the data

- How to blind

- Using the EDA to help with blinding

- Indicating the blinding status on your EDA diagram

Why is blinding important?

Blinding is essential to ensure robust findings. Many recent studies have shown that publications report a greater treatment effect when their studies did not use blinding, suggesting they have overestimated the effects.

Blinding is a research strategy that limit bias. It involves keeping the people who conduct the experiment, assess the outcome(s) and collect and analyse the data unaware of the treatment allocation. By expecting a particular outcome from an experiment, you can unintentionally influence the experiment or interpret the data in a way that supports your preferred hypothesis.

You can blind different stages of the experimental process. This may require additional help from others, for example a surgeon to perform interventions, a technician to code the treatment syringes for each animal, or a colleague to code the treatment groups for the analysis. Ideally, an experimenter should be unaware of the treatment allocation from the start of the experiment until after the results have been analysed.

In reality it is not always possible to blind all steps in an experiment. However, it should always be possible to conduct at least some of them blind. Any amount of blinding you introduce into your experimental design will improve the robustness and reliability of your findings.

The British Pharmacological Society has created an animated video introducing the concept of blinding and how it can be used at different stages of an experiment to reduce bias.

Allocation concealment and blinding during and after intervention

Allocation concealment means that the people assigning the animals to intervention groups are unaware of the allocation sequence (which treatment will be allocated to each individual animal), until the moment of assignment. It is used with randomisation to minimise selection bias. Selection bias introduces systematic differences in the characteristics of animals allocated to treatment groups. Allocation concealment enables blinding and, in an ideal scenario, the allocation sequence should not be revealed to the people conducting the experiment until the data has been analysed.

Often in animal research, animals are allocated to a group as they receive their intervention, so this section will also cover blinding during and after the intervention. This means that the people administering the treatment are unaware of which treatment each animal receives. For example, for a pharmacological intervention, the drug can be prepared by an independent investigator and labelled for each experimental unit. This ensures that the person administering the drug knows which experimental unit receives which syringe but does not know what each syringe contains. For a surgical intervention, the surgeries can be performed by an independent investigator and the animals coded to ensure the surgery they received is concealed from the researcher who will carry out the rest of the experiment.

Blinding during conduct of the experiment

Animal care staff should also be blinded to treatment to allow consistent care across all animals. Ideally welfare interventions should be applied the same way regardless of which intervention animals received. There may be some cases where this is not appropriate, for example in some studies the intervention being tested could induce a transient welfare issue which would be tolerated for a limited time in treated animals but not in control animals. A harm-benefit analysis examining the risk of introducing bias vs the risk of harm to the animals should be undertaken and a plan put in place before experiments start. Procedures should also be put in place to ensure that information on which intervention each animal received can be made available to animal care staff in cases where this knowledge affects welfare decisions.

Blinding during result assessment

Blinding is especially important during the assessment of the results, particularly if there is a subjective element to assessing the treatment outcomes – for example, when assessing behavioural changes or reading histological slides. The person assessing the outcome should not know which intervention each animal has received (i.e. the group allocation) or which animals are grouped together. Randomising the order of examination can help with this.

Sometimes the person assessing the outcome cannot be blinded to the group allocation. A common example of this is if there are obvious phenotypic differences between groups of genetically modified animals. You can mitigate this by, for example, recording the behaviours and sending them to a third party, with no vested interest in a specific outcome and who does not know whether the transgene should improve or worsen the outcome. This approach at least counters the expectation of results going in a particular direction.

Blinding during analysis of the data

Blinding is perhaps easiest to implement during data analysis. The person analysing the data needs to know which animals are grouped together to make group comparisons, but should not know what treatment these groups received. This is important as the analyst makes many semi-subjective decisions such as applying data transformation to outcome measures and handling missing data and outliers. These decisions could be biased by knowing whether animals received a control or an active treatment, and the analyst could subconsciously affect the outcome of the study.

How to blind

Blinding involves help from another person, a colleague or a collaborator for example. Depending on the specific experiment, you can implement blinding in different ways.

The most common method of blinding is to use numerical or alphanumerical coding. For example, for a pharmacological intervention, a colleague can use the allocation sequence to code vials or syringes with a number for each animal. The drug coding is recorded and placed in a sealed envelope to be revealed at the end of the experiment. If the drug and vehicle are distinct in appearance, the contents of the vial can be masked using opaque tape or coloured syringes to conceal the appearance. A similar method can be applied to cages of animals, which can be coded to receive specific treatments or diets.

For a surgical intervention, surgery can be performed by an independent investigator and the animals coded to ensure the surgery they received is concealed from the investigator that carries out the rest of the experiment. If the surgery must be carried out by the main investigator, then the animals can be recoded by an assistant after the surgery. This allows the main investigator to be blind to later stages of the experiment, such as assessment and analysis.

Colour coding can also be used to disguise which intervention animals are receiving. It is important to note using colour coding means you will know which animals have received the same intervention. While it does reduce bias you may still be able to see patterns in the data or animals. For this reason, this method is not ideal and is considered partial blinding.

You should create a blinding plan when planning your experiment. This should outline who will be aware (and unaware) of group allocation at each stage of your experiment. If different people will be blinded at different steps you will need to plan how the information regarding group allocation is handed over, and whether recoding is needed (e.g. does someone need to go from being aware of group allocation to being unaware?). The blinding plan should include where the ‘key’ that unblinds people is kept, and who has access to it. Also consider giving access to the ‘key’ to more than one person in case personnel leave the project part way through.

Your blinding plan should also cover welfare management. This includes outlining:

- Who will be unblinded if welfare issues arise.

- Where they will find the ‘key’ to unblind themselves.

- What action they need to take.

If possible, include examples of specific welfare issues that might occur (e.g. a known welfare issue for that strain, species or genotype).

Using the EDA to help with blinding

The EDA can help you ensure that intervention, measurement and analysis are carried out blind. The EDA can generate a randomisation sequence containing the group allocation for allocation concealment, based on your EDA diagram (see allocation section). This sequence can be sent directly to the person who will help you with blinding, who ideally only reveals the allocation sequence once the data have been collected and analysed.

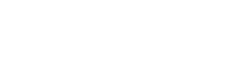

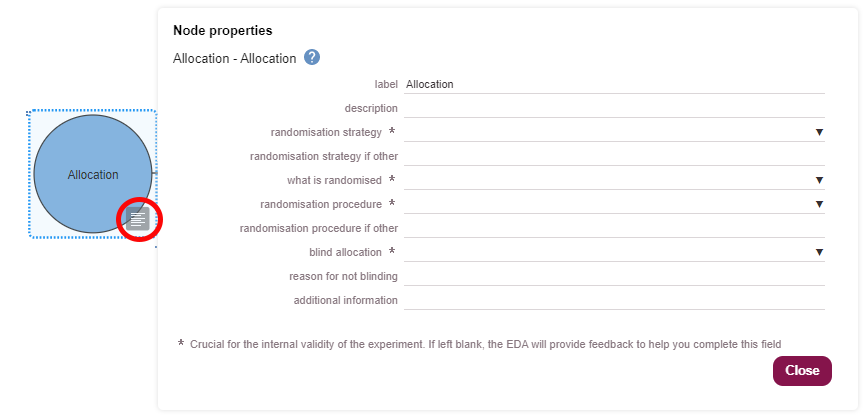

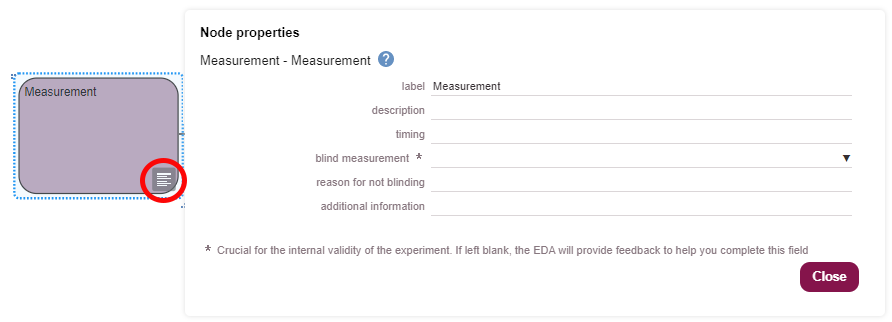

Indicating the blinding status on your EDA diagram

You can indicate the blinding of different stages of your experiment in the EDA. Blinding information should be provided in the properties of the allocation, measurement and analysis nodes, as shown in the images below. If any of these three stages was not carried out blind (i.e. you are aware of the group allocation of each animal, or aware of which animals are grouped together), you can record the reason why blinding was not possible.

References

Bebarta, V, Luyten, D and Heard, K (2003). Emergency medicine animal research: does use of randomization and blinding affect the results? Acad Emerg Med 10(6):684-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2003.tb00056.x

Cordaro, L and Ison, JR (1963). Psychology of the Scientist: X. Observer Bias in Classical Conditioning of the Planarian. Psychological Reports 13(3):787-789. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1963.13.3.787

Doig, GS and Simpson, F (2005). Randomization and allocation concealment: a practical guide for researchers. J Crit Care 20(2):187-91; discussion 191-3. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2005.04.005

Karp NA, Pearl EJ, Stringer EJ, Barkus C, Ulrichsen JC, Percie du Sert N (2022). A qualitative study of the barriers to using blinding in in vivo experiments and suggestions for improvement. PLOS Biol. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3001873

Krauth, D, Woodruff, TJ and Bero, L (2013). Instruments for Assessing Risk of Bias and Other Methodological Criteria of Published Animal Studies: A Systematic Review. Environmental Health Perspectives 121(9):985-992. doi: doi:10.1289/ehp.1206389

Macleod, MR, et al. (2009). Good laboratory practice: preventing introduction of bias at the bench. Stroke 40(3):e50-2. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.525386

Moher, D, et al. (1998). Does quality of reports of randomised trials affect estimates of intervention efficacy reported in meta-analyses? The Lancet 352(9128):609-613. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)01085-X

Polit, DF (2011). Blinding during the analysis of research data. Int J Nurs Stud 48(5):636-41. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.02.010

Rosenthal, R and Fode, KL (1963). The effect of experimenter bias on the performance of the albino rat. Behavioral Science 8(3):183-189. doi: 10.1002/bs.3830080302

Schulz, KF, Altman, DG and Moher, D (2002). Allocation concealment in clinical trials. JAMA 288(19):2406-2406. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.19.2406-JLT1120-4-1

Schulz, KF, et al. (1995). Empirical evidence of bias. Dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. JAMA 273(5):408-12. doi: 10.1001/jama.273.5.408

Schulz, KF and Grimes, DA (2002). Allocation concealment in randomised trials: defending against deciphering. Lancet 359(9306):614-8. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)07750-4

Tuyttens, FAM, et al. (2014). Observer bias in animal behaviour research: can we believe what we score, if we score what we believe? Animal Behaviour 90:273-280. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2014.02.007

van der Worp, HB, et al. (2010). Can animal models of disease reliably inform human studies? PLOS Med 7(3):e1000245. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000245

Vesterinen, HM, et al. (2010). Improving the translational hit of experimental treatments in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 16(9):1044-55. doi: 10.1177/1352458510379612